The Non-Continuous Monkey in its Maze

On the Bus

…from Woodstock to New York last fall—to visit Loisaida on the “Lower East Side” to site an enactment of the Post-Cuban Cabaret—the artist Omar Pérez and I were shooting the breeze about Zombies and the vast hypnosis into which many of our fellow travelers in the throes of being human are stumbling or have fallen. (It’s an old story, though recently—and even setting aside the big “nature of sleep”—it seems to have taken a big leap in its power and complexity due in no small measure I feel to—among many others unnaturally—the father of public relations and public manipulation (propaganda) Edward Bernays, the shadow man Doctor Sax, down the alley dealing dope, in so many words, who invented the term “psychological warfare.” Of his Ivory Soap Prototophron campaign, Bernays writes: “As if actuated by the pressure of a button, people began working for the client instead of the client begging people to buy.” That alchemy, coupled with the ubiquity of hands-reach and instantaneous media via cell is sicking.)

The Coconut

And one way to talk about it is what Omar said then on the bus about the myth of the monkeys and the Einstellung Effect wherein: villagers, broadly speaking, catch monkeys by cutting a hole in a coconut and putting something monkeys want inside it, though making the hole just wide enough that they can’t get it out without letting go—so the monkeys walk around dragging coconuts.

We were near the back of the bus, not too crowded, and a beautiful day outside sunny at the end of summer—slumped in our seats with Omar at the window though on the driver’s side so over the Interstate—and Omar doesn’t like roads so much, or rather hurtling hunks of metal killing animals—and Omar never quite slumps—and looking over across the aisle witness a woman on her cell phone totally connected and watching intently, participating in this world that seemed very foreign to our own at that moment—the focus of her gaze away—when I said, “She can’t get her hand out of the coconut.”

I don’t think Omar had connected it—I think I actually make it—which is rare—and we looked at each other in the way you may with a friend to pierce through laughter what laughs—she had in ear phones—and figured it out quickly from there that on my god, she’s on the coconut!

The Takeaway

And so I can’t look at cell phones anymore without perceiving a coconut; and I advocate you form the same button.

I’m a big fan of this coconut association and feel it could be loaded into a Bernaysian cannon to explode us back from the brink of ourselves.

I should also say that recently I heard the tail end of a radio interview with Arthur Firstenberg talking about wireless microwave radiation in which I thought I heard “coconut.”

And remember “on the coconut” is maybe the best we can ask—at the edge of “in,” with a hand tightening around us (which I fear is true for many and sometimes myself, when I can find it).

Catskill Sieve: Mojo Dojo 1

Chuck Berry on the Road to Perseus Cluster

The B-Flat at a Cosmic Corner

It turns out black holes emit a sound—or the one centered in the Perseus cluster of galaxies about 250-million lights years away (or at the edge of numbers close to the edge of Cantor’s proposition of the existence of an “infinity of infinities”) does—a B-flat 57 octaves below middle C as recorded in ’03 at NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

That hum is the deepest sound in the known cosmos in numerical notation written 262 Hz / 2^57, or about 1.818 femtohertz—take that!—completing one cycle every 17.44 million years, or say one hundredth of the age of the universe as we know it.

The B-flat within human-ear range is 466.164 Hz and sounds like the “go go” in the original recording of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.”

Chuck Berry’s B-Flat

Berry grew up in St. Louis, not Louisiana, and while his beginnings were hard—including time for armed robbery—he could “read and write”: moreover he went to school to become and earn a living as a beautician. We all should. Otherwise “Johnny B. Goode” is pretty fused to Berry’s biography and experience surging out the heart of the African-American suck—and it was originally “that little colored boy can play…”—not “country.” (It was changed to get anglo-American attention.) He probably composed the song with Johnnie Johnson, from which the “Johnny” derives (Johnson gave Berry his break into music)—and the “Goode” from the avenue in North St. Louis on which his childhood home was located (since razed). So it’s got sinew, this song written in Berry’s 20s and the start of a career the telemetry of which would place Berry in the Rolling Stone’s “100 greatest artists of all time,” fifth between the Rolling Stones and Hendrix, which I guess obvious to many.

What’s more telling maybe then the biographical resonance is the song’s archetypal one, harking to origins in the Delta and so to a sense of calling. You know it was Berry’s choice to place him in Louisiana, not “North Saint Louis” (same syllabic-stress count and could work like “country” for “colored”). That’s where one feels the B-flat, which Berry’s use of may have derived from Johnson’s piano—vs. guitar—keys. (According to Spin, Strangeness and Charm, while viable to use B-flat to compose on piano, in standard guitar tuning it’s an awkward key and usually the song’s rendered in A, say.)

Yet in the act you can’t not hear the “B.” for “being” obviously—”Johnny be”—connecting to the hum of the hive in the middle at least of be’s if not cosmos. The “Goode” be good—to be out of and at one’s start (Goode Avenue) and rock nativity—to hear it and have goods to call back to “be”—our human aspiration equals Chuck Berry.

A Stretch

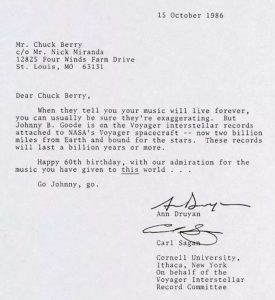

…and maybe it is yet I want to feel the one event between the edge of the universe calling and Berry responding. And it’s what I’d wish each us. Carl Sagan might have felt it facilitating the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” on the Voyager’s Golden Record—its only rock song, accompanying among others Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos—with Sagan writing to Berry it “…will last a billion years or more” (as below).

Here below are photos of the Perseus cluster juxtaposed with the house where Berry wrote “Johnny B. Goode”: 3137 Whittier Street near his birthplace.

We want that sense that both soundings are equidistant simultaneous touching humming you can’t see the edge of yet according to Atlas Obscura there’s a faint “B” presumably for “Berry” still visible on the awning over the front porch.

On the Clave

Having spent time enough with Omar to learn how to breath better and hear

—

or pace or gap

—

I here perform some works from memory to see how it finds sounds and feels

—

with the clave, which I sense acts as a dowser like the triad branch we use to find water, as I imagine it trembling at the end where the fork joins the word “clave”

—

and so the thing, which is two sticks one hits together

—

in fact derives from *klau– meaning “hook, crook” (Proto-Indo-European root) and “crooked or forked branch” (used as a bar or bolt in primitive structures

—

though one may imagine too for finding a water source).

The word “close” comes from it.

The clave’s more common meaning, and its musical application, is “key,” like the central stone in an arch (keystone, or what holds arch up), and in a group of musicians is used to keep time.

Here I am mostly playing the son clave.

I am accompanied on paperboard by Matthew Morse what passes through an arch that does not exist.

Many thanks to Bruce Weber who hosted the Hudsonics performances; and to David Schell of Green Kill.

Onward!