The B-Flat at a Cosmic Corner

It turns out black holes emit a sound—or the one centered in the Perseus cluster of galaxies about 250-million lights years away (or at the edge of numbers close to the edge of Cantor’s proposition of the existence of an “infinity of infinities”) does—a B-flat 57 octaves below middle C as recorded in ’03 at NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory.

That hum is the deepest sound in the known cosmos in numerical notation written 262 Hz / 2^57, or about 1.818 femtohertz—take that!—completing one cycle every 17.44 million years, or say one hundredth of the age of the universe as we know it.

The B-flat within human-ear range is 466.164 Hz and sounds like the “go go” in the original recording of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.”

Chuck Berry’s B-Flat

Berry grew up in St. Louis, not Louisiana, and while his beginnings were hard—including time for armed robbery—he could “read and write”: moreover he went to school to become and earn a living as a beautician. We all should. Otherwise “Johnny B. Goode” is pretty fused to Berry’s biography and experience surging out the heart of the African-American suck—and it was originally “that little colored boy can play…”—not “country.” (It was changed to get anglo-American attention.) He probably composed the song with Johnnie Johnson, from which the “Johnny” derives (Johnson gave Berry his break into music)—and the “Goode” from the avenue in North St. Louis on which his childhood home was located (since razed). So it’s got sinew, this song written in Berry’s 20s and the start of a career the telemetry of which would place Berry in the Rolling Stone’s “100 greatest artists of all time,” fifth between the Rolling Stones and Hendrix, which I guess obvious to many.

What’s more telling maybe then the biographical resonance is the song’s archetypal one, harking to origins in the Delta and so to a sense of calling. You know it was Berry’s choice to place him in Louisiana, not “North Saint Louis” (same syllabic-stress count and could work like “country” for “colored”). That’s where one feels the B-flat, which Berry’s use of may have derived from Johnson’s piano—vs. guitar—keys. (According to Spin, Strangeness and Charm, while viable to use B-flat to compose on piano, in standard guitar tuning it’s an awkward key and usually the song’s rendered in A, say.)

Yet in the act you can’t not hear the “B.” for “being” obviously—”Johnny be”—connecting to the hum of the hive in the middle at least of be’s if not cosmos. The “Goode” be good—to be out of and at one’s start (Goode Avenue) and rock nativity—to hear it and have goods to call back to “be”—our human aspiration equals Chuck Berry.

A Stretch

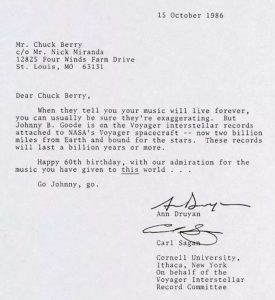

…and maybe it is yet I want to feel the one event between the edge of the universe calling and Berry responding. And it’s what I’d wish each us. Carl Sagan might have felt it facilitating the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” on the Voyager’s Golden Record—its only rock song, accompanying among others Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos—with Sagan writing to Berry it “…will last a billion years or more” (as below).

Here below are photos of the Perseus cluster juxtaposed with the house where Berry wrote “Johnny B. Goode”: 3137 Whittier Street near his birthplace.

We want that sense that both soundings are equidistant simultaneous touching humming you can’t see the edge of yet according to Atlas Obscura there’s a faint “B” presumably for “Berry” still visible on the awning over the front porch.